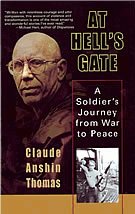

At Hell’s Gate: A Soldier’s Journey from War to Peace

Chapter headings:

- 1. The seeds of war

- 2. The light at the tip of the candle

- 3. The bell of mindfulness

- 4. If you blow up a bridge, build a bridge

- 5. Walking to walk

- 6. Finding peace

Selected excerpts:

“When I entered a rehabilitation center for drug addiction in 1983, I was able to stop using drugs, stop drinking. After I stopped using drugs and alcohol, the obvious intoxicants, I began to be able to learn what the other intoxicants were that were preventing me from looking at myself. And I began to stop those things also. I stopped using caffeine, I stopped using nicotine, I stopped eating processed sugar, I stopped eating meat, I stopped going from one relationship to another. I kept coming more and more back to myself, in my commitment to heal, even though I did not understand (in any intellectual way) what it was I was doing.”

“In 1990 it became impossible for me to hide from the reality of my Vietnam experience any longer. Vietnam was not just in my head; it was all through me. I had talked intellectually about Vietnam, but I had never fully opened myself to the totality of this experience. Now the pain reached a point where it was so great that I wanted only to hide from it, to run from it yet again. My first thought, of course, was to get drunk. When I drink, it covers the pain like a blanket. But under the blanket, inside me, is full of barbed wire; every time I move, it cuts at me, tears my skin. When I drink, I have the illusion that I have put a buffer between my skin and the barbed wire, but this is not the truth; when I am anaesthetized, I am just not so aware of the ripping and tearing.”

“Well, this time I didn’t have that drink. Instead I ended up at a Buddhist meditation retreat for Vietnam veterans led by the Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh.” (pp. 35-36)

“I believed that it was me who was choosing to take drugs, drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes, rather than the seeds of suffering in my life choosing for me. I lived under the illusion of having a choice.” (p. 63)

“After I went through drug and alcohol rehabilitation in 1983, I stopped turning to intoxicants (the obvious forms). Looking back, this is probably the single most important event in my life, because it gave me the opportunity to experience my own life and to experience it directly – the only place from which healing and transformation can begin to take place.” (p. 153)

© 2004 Claude Anshin Thomas

Order this book online at Amazon

Reviews posted:

Paul –

This book came highly recommended by Bill Alexander (author of Cool Water), and justifiably so. It is a powerful, moving account of a distinguished Vietnam veteran whose path to recovery from the horrors of war ultimately leads him to take the robes of a Buddhist monk. It is primarily a story of war and peace, though alcoholism and addiction are ever-present threads (as the selected excerpts above illustrate). His father was a soldier and an alcoholic, and history repeats itself when the author enters military life and quickly starts to use alcohol as an anaesthetic. As one would expect, there are some shattering anecdotes. I won’t recount them here, as that may spoil the impact of the story for you. So many times I said to myself “And I thought I had problems with my traumatic marriage breakup, moving countries etc. Pah!” Some of these combat experiences were so traumatic they were repressed, and it was only his Buddhist work many years later that brought them back to awareness. Only then could he see how key post-war events in his life had been influenced by these experiences, without him having been aware of it. I was reminded of the saying ‘The only way out of suffering is through it’, and by confronting his past, he moved from being subconsciously driven by his negative conditioning, to finally attaining awareness and freedom. There is a revealing discussion of Thich Nhat Hanh’s movement, showing its strengths and weaknesses (in fairness it should be stated that his influence is profoundly positive). The book’s key message is that real peace doesn’t magically fall out of political ideology or social reform, it can only be won by looking at the seeds of war within ourselves, our insecurities, fears, jealousies, greed etc He also kept looking outside himself for a solution to his problems, but it was only when he finally looked inside, that he started to get some answers. The writing style is very disciplined, direct, clean, and succinct – he doesn’t wallow in the war experiences. The balance between the autobiographical passages and broader discussion and analysis is also excellent. Ultimately this website should be about inspiration – resources that inspire us to practice. This is one such resource.

Michael –

From a truly harrowing and at times violent account of his active service in Vietnam, to taking the robes of a Zen monk and being a healing force for peace, this is a book that moved me deeply. Although I don’t even pretend to know or fully comprehend many of the direct personal experiences of which he speaks, I can nonetheless only agree most wholeheartedly when he asserts that all of us have our own Vietnam, in one form or another. Indeed each of us suffers, as the first Noble Truth teaches us, and each of us has our own private hells or spheres of violence. What moved me so deeply in this book was the author’s obvious courage in facing up to this past, his reflections and subsequent understanding of what brought him to that point in the first place, and his choice to later help liberate others who had been through similar experiences to himself. But most of all what moved and inspired me is his understanding that sometimes there are residual difficulties that simply need to be lived through. One of my own favourite sayings in recounting my own story is that I believe that no matter how good recovery gets, and indeed I have a lot to be grateful for these days, that recovery its not about getting a perfect life. I believe, instead, that recovery is more about learning how to live within an often imperfect one. Simply being fully present with what is, and being OK with that. The post-traumatic stress the author suffers from his experiences in Vietnam is not magically cured. He still has sleeping difficulty, gets flashbacks, and is haunted by the faces of the dead. Yet, through facing and indeed somewhat even embracing his past, the author has profoundly changed his life, and the lives of others for good. It’s as he describes, “Peace is not the absence of conflict; its the absence of violence within conflict”. I would recommend this book as an absolute must for anyone who has suffered through the personal violence of war and conflict, but for the rest of us and certainly for myself, it put my own life and rather petty problems by comparison rapidly into perspective. It reminded me that both healing and peace need to start with me, and of my responsibility to help others. With the author’s obvious deep insight and understanding comes a profound and valuable lesson for us all.