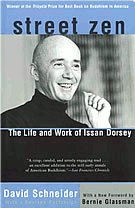

Street Zen: The Life and Work of Issan Dorsey

Chapter headings:

- Foreword by Roshi Bernie Glassman

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Mountain Seat

- 2. A Little Bit Different

- 3. Descent into Heaven

- 4. Boy So Pretty

- 5. Baddest of the Bad Chicago Queens

- 6. Go Ask Alice

- 7. Beginner’s Mind

- 8. White Bird in Snow

- 9. “You Get What You Deserve, Whether You Deserve It or Not.”

- 10. Santa Fe

- 11. Opening the Door

- 12. Death at the Door

- 13. The Greatest Teacher

- Postscript

Selected excerpts:

“At the same time, Issan began to want a way of working with other parts of society, the parts that he had lived in so long, the gutter. He was unable to ignore the homeless kids in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district, young addicts, dealers, runaways, and prostitutes. He began talking about a soup kitchen down there, throwing the idea around in conversation, and making preliminary inquiries about town. He and Baker-roshi even went to inspect an abandoned bathhouse as a possible site. His interest later led him to Ruth Brinker. Between them they put together a food-service program for the homeless called Open Hand, which runs in a much-expanded form today…[Peter Coyote:] “One way Issan allowed himself to be authentic was that he described himself as a faggot speed-freak cross-dresser, and at a certain point if you do that, you realize that that definition is a joke. No definition can contain a whole person, but where most people would define themselves as the director of this or that and hide the faggot speed-freak cross-dresser, Issan fronted that, so what kind of airs could you put on?” (pp. 127-128)

“The encounter with death begins at birth, not when we are actually sick and dying. Baker-roshi, my teacher, had me speaking about the fact that it should be our practice to keep in front of us all the time, ‘I certainly am going to die. I certainly am going to die.’ When I was listening to his lectures, I always said, ‘Oh I understand that. I know that.’ Because I had been close to death many times in my life. Also, I had already begun some minimal work with people with AIDS. This is before living at Hartford Street Zen Center. In my mind, I felt I understood what that meant: ‘I certainly am going to die.’”

“But lo and behold, when I had my HIV test in Santa Fe, and it was positive, the relationship [chuckling] with ‘I certainly am going to die’ changed. Radically. And then all along the way. You know the first time I became sick…”

“After I went through those initial changes and came back to San Francisco, I felt quite healthy and had a lot of energy. I was helping to establish more the practice place at Hartford Street Zen Center, giving classes and lectures, and thinking about how we might involve ourselves with the AIDS epidemic. We made a lot of great changes at Hartford Street then, and it took a lot of energy.”

“In my lecture book here, I see that in the last lecture I gave at Santa Fe, I discussed the Five Fears. I must have discussed them because they’re written down here: Fear of Loss of Livelihood, Fear of Loss of Reputation, Fear of Unusual States of Mind, Fear of Death, and Fear of Speaking Before an Assembly. Probably I’m experiencing all five of these fears at this point, right now. Except Loss of Reputation – it’s too late for that.” (pp. 185-186)

© 1993, 2000 David Schneider

Order this book online at Amazon

Reviews posted:

Paul –

Street Zen is similar in some ways to At Hell’s Gate in providing an inspiring tale of self-transformation that can motivate us to practice. The transformation in the case of Issan Dorsey is from a self-described “faggot speed-freak cross-dresser” into a respected Zen teacher. As a tale of excess, the initial ‘drunkalogue’ part of his story can hold its own against the stiffest competition. This makes the juxtaposition with his subsequent Zen life all the more dramatic. The discussion of his gradual conversion to Buddhism and involvement with the San Francisco Zen Center also covers in some detail the 1983 Richard Baker scandal in which Issan became embroiled (this is referred to in Katy Butler’s essay and she receives a couple of mentions in the book). The most important part of the book for me was Issan’s charitable work in the community, and how in the face of criticism he turned his Zen Center into an AIDS hospice. We need more Issan Dorseys, people who can serve as models of ‘engaged’ Buddhism. The final section dwells on our mortality, and confronting life with a terminal illness. I found myself more touched by this story than I had anticipated. In a branch of Buddhism often known for its icy formality, his warmth, self-deprecating humour and gentle non-conformism were wonderful. There is little concrete discussion of the way he applied Zen practice to recovery (in the fashion provided by Mel Ash and William Alexander). However, the obvious retort is that these simple stories of cooking in the communal kitchen and caring for people were his practice.

Michael –

David Schneider was ordained as a Zen Priest in 1977, and Street Zen is a story written from the author’s own long friendship with Issan Dorsey and a dozen interviews he conducted with him. The Life of Issan Dorsey is nothing short of remarkable. His story includes being a drag queen in San Francisco in the 1950’s, to the worst excesses of drug and alcohol addiction, and finally the LSD experiences that set him on the path to Zen. In 1989, after twenty years of Zen practice, he became Abbot of San Francisco’s Hartford Street Zen Centre, a place where he also founded the Maitri Hospice for AIDS patients. After caring for those who died from AIDS, the tables were turned and Issan himself passed away from the disease in 1990, surrounded by friends and supported by his Zen community.

Street Zen is a testament to the transformative power of Buddhist practice, and to a man who committed his later life to service in various forms. In many ways he was a shining example of compassion in action and the term ‘engaged’ Buddhism. However, whilst this book is a truly valuable account of one man’s life, those seeking specific details as to how exactly one may overcome addiction problems themselves will be disappointed. For though clearly written and packed with obviously well researched details, no explanation is given in the book as too how exactly Issan Dorsey dealt with his addictions. That is, of course, aside from the fact that in the exploration of Zen Buddhist meditation and practice, he realised that he needed to make such changes in his life. Although typically Zen in the sense one could simply say “meditate and practice”, many in recovery might seek a more detailed explanation than this.

I would have no hesitation in recommending Street Zen to others who might be interested in such a story. But if you approach this book with the hope that it may shed further insight into a Zen approach to recovery, you will be disappointed. If this is your objective, I would direct you to either The Zen of Recovery by Mel Ash or Cool Water by William Alexander. But if you simply want to be inspired and moved, this book is for you.